Graduate instructor Deja Beamon reflects on the importance of inclusive teaching in her classroom:

“For me, inclusivity starts with making the classroom a comfortable, supportive space for students to be themselves. Often students assume what learning looks like and it becomes harder to identify what they may be needing as individual learners.

“I always include multi-method learning techniques. Often our classrooms are mislabeled “seminar” or “lecture,” but I instead approach the classroom as a workshop space, where I model how and why things are important and encourage students to form their own entries into knowing. By using multi-method techniques, students see the expansive ways to practice and obtain knowledge.

“Lastly, I check in with my students frequently. I never assume understanding especially as my course builds. I also promote peer learning so they can check in with each other, too."

Some instructors teach content directly related to DEIJ (diversity, equity, inclusion, and justice) every term, while others rarely teach such content explicitly. But because our classrooms are made of people, and because people bring with them a range of backgrounds, experiences, and emotions, it is best practice for every educator to consider issues of diversity and inclusion in their classrooms.

Reflect... Your class is made up of many individuals with different backgrounds, needs, and learning preferences. How do you make your classroom or online course welcoming, inclusive, and supportive for all students?

Diversity in the Classroom

When reflecting upon diversity in your class, it is important to consider the following.

- Every class includes individuals with diverse identities and experiences.

- Every educator is responsible for creating a learning environment that helps students feel included.

- Reducing marginalization and increasing representation improves student learning outcomes.

All classes are diverse.

Students bring identities, opinions, and emotions with them to your classroom or online course. Some aspects of diversity are visible and some are not, but they always shape student experiences and learning, often in positive ways (Walton & Cohen, 2011). A diverse classroom where students have structured opportunities to learn from each other can lead to better problem solving and mirrors real-life applications in future job contexts (Johnson, D., Johnson,R., & Smith, 2014). Acknowledging the lived experiences, interests, and prior knowledge of students lets us address misconceptions, explore what counts as disciplinary evidence, and connect course material to the outside world. As educators, we are also part of the learning environment, and our identities and biases impact that space as well.

Reducing marginalization improves learning.

The experiences we and our students bring to the classroom carry implicit biases that sometimes surface during classroom interactions (Boysen & Vogel, 2009). As coursework challenges our biases, intense emotions and even conflict can arise. In other cases, implicit bias can result in microaggressions that marginalize individuals in the class. When students (or teachers) are affected by bias, they lose opportunities to learn—neural processing is used up with emotion instead of learning (Steele, 2011). When students feel supported, however, that cognitive load is available for processing complex topics and problems.

"Value-free teaching does not exist."

- W.J. McKeachie, 2002

Representation matters.

Research on student motivation shows a significant relationship between a feeling of belonging and improved course outcomes (Walton & Cohen, 2011). When students have a sense of belonging, they feel respected, accepted, valued, included, cared for, and that they matter—in your course, at the university, and in their major or career path.

Regardless of discipline, students are more likely to succeed when they see their identities, experiences, and interests reflected in the course. If we do not take an inclusive approach to choosing course materials in which diverse students can see themselves represented, we reproduce biases that favor some groups of students over others. This lack of representation sends implicit signals about which groups of students can expect to be successful in our fields, and which groups cannot.

Choosing inclusive content is more intuitive in some disciplines than others, but every course can increase its range of representation (Plank & Rohdieck, 2007). Looking at our course content, we need to ask ourselves: Who is included and who is excluded?

Read more about sense of belonging in college learning environments.

Every educator has a responsibility for inclusion.

The way we shape the learning environment can help us leverage diversity to improve learning outcomes. By anticipating activities, discussions, and readings that could be controversial or difficult to navigate, we can decrease the effects of bias by preparing students with appropriate language to use (Barkley, Cross, & Major, 2014). Even if a class does not deal with “diversity content directly, the voices we include in our content shape how students frame their learning” (Plank & Rohdieck, 2007).

Most of us would like to imagine that our courses feel inclusive to students, but research suggests the most common climate in college classrooms is implicitly marginalizing (Ambrose et al., 2010). The good news is, there are a range of concrete approaches educators can take to create more welcoming and positive learning environments. By acknowledging student emotions, allowing for multiple perspectives, and setting ground rules for respectful interactions, we create more equitable spaces for students to meet our learning goals (Walton & Cohen, 2011).

Intersectionality and Teaching Practice

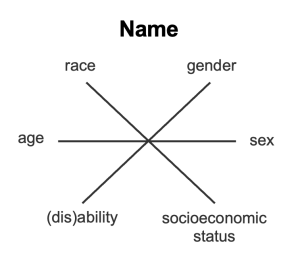

As instructors, we must consider how our own identities impact our teaching and how students' identities impact their learning experience. Each of us has a quality along axes of difference such as gender, race, class, sexual orientation, nationality, language fluency, and (dis)ability. That means each of us has a gender, a race, a class, a sexual orientation, a nationality, and so forth. This approach to identity, which recognizes that we experience our lives at the intersections of axes of difference, is called intersectionality.

Social Identity Wheels

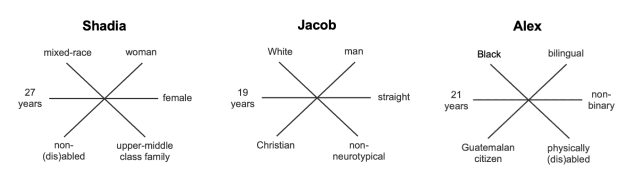

We will use a visual tool called the “social identity wheel” for thinking about the intersectional qualities that we all have. This identity wheel template and the examples below were inspired by the University of Michigan's Social Identity Wheel activity.

When creating an identity wheel, you can include however many spokes or axes of difference you like. As you look at these wheels, keep in mind that each person is at the center of their map. That is, each person has experiences at the intersection of their race, sex, gender, class, sexual orientation, or other listed factors. If any one of those spokes of identity were different, their whole identity may be impacted. People are not encompassed by one spoke, like race or gender or sexual orientation; they are not just “white” or “a woman” or “straight.” Instead, they are every one of their qualities combined.

Check out these example social identity wheels.

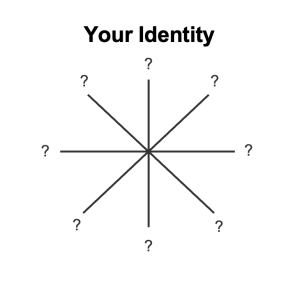

Social Identity Wheel Exercise

Your experience of your “identity wheel” can change from moment to moment. Perhaps at some points your nationality is more present in your mind but at others your sexual orientation is more present. In other words, your experience of identity can fluctuate given the social contexts and environments you find yourself in throughout the day, and throughout the course of your life.

Try it...

- Map yourself on a blank wheel like the one pictured here, and have your students perform the exercise as well. What do you notice? What qualities seem most significant for you and your students to include?

- Now imagine that one spoke on your wheel were different. For instance, list something else for your socioeconomic status or gender. Ask yourself (and your students) to ponder how one change could affect your entire experience of your identity.

Keep in mind that every student comes to your class with a multifaceted "identity wheel," and each with their own experience of the qualities that are central to their identity. How will you foster a learning environment that welcomes a wide range of individuals with this complexity? How will you avoid assuming that any of your students are just “one” thing (just their race, gender, or nationality)? How will you encourage students to understand and value each other’s complexity as well?

Note: Intersectional approaches to identity are deeply indebted to the work of Black feminist thinkers, such as bell hooks, Audre Lorde, Sylvia Wynter, Toni Morrison, and Saidiya Hartman. Explore scholarship on intersectional identity and other themes at the Black Women's Studies Booklist.

Dive deeper into the Social Identity Wheel activity and other inclusive teaching resources at the University of Michigan's Inclusive Teaching at U-M site.

Designing for Every Student

Instead of assuming (falsely) that all your students are the same, it is best practice to design your course outcomes, materials, and assessments in ways that promote equal access and a positive experience for all individuals. Validated by extensive research, the Universal Design for Learning (UDL) framework is an approach to planning and delivering your course with inclusivity and access at the forefront.

Implementing UDL can help you avoid making empty statements that do not truly address your classroom climate and challenges. Scholar Sara Ahmed calls such statements nonperformative; for example, offering “thoughts and prayers” without taking concrete steps to address challenges you’re experiencing with students (Ahmed, 2006). Instead of simply repeating a boilerplate statement about diversity on your syllabus, incorporate intentional strategies that make your course content more inclusive and accessible. Some examples are including multiple means of representation, providing captions for all your course videos, and offering transcripts of all the audio recordings you use.

Learn about UDL and how to apply it in your course in Universal Design for Learning: Planning with All Students in Mind. Explore additional methods to support all students in Supporting Student Learning and Metacognition.

Develop Your Inclusive Teaching Practice

If you're ready to learn and apply concrete strategies to make your course more inclusive, look into the Inclusive Teaching endorsement offered by the Michael V. Drake Institute for Teaching and Learning. As a participant, you will select and attend six or more professional learning opportunities that have been identified as meeting the following endorsement outcomes:

- Define inclusive teaching.

- Discuss research on how effective inclusive teaching strategies impact learning.

- Practice identifying opportunities and proactive measures for inclusive learning environments.

- Identify challenges and supports to inclusion within current courses.

- Plan specific inclusive strategies to apply in your own teaching this term.

See also the Learning Opportunities linked below and the inclusive resources for educators provided by the Drake Institute. If you need individualized guidance on a specific problem or concern in your course, visit our Teaching Support Forms.

Summary

Teaching is a challenging activity that calls for a varied skillset, frequent reflection, and the flexibility to adapt and change in response to student needs. Intentionally designing your courses and classrooms to be more inclusive of marginalized identities is a responsibility that educators across all disciplines share. The research shows that taking steps to make marginalized students feel included benefits those students especially, but also improves achievement of learning outcomes for all students in class.

As you are reflecting upon how to make your course inclusive, remember that

- All classes are diverse. All students bring their identities, opinions, and emotions with them to the classroom, some visible and some not, and these aspects of diversity shape their experiences and learning in your course.

- Reducing marginalization improves learning. Bias, microaggressions, and conflict in class negatively impact learning. When students feel a sense of belonging, they can better attend to learning and have increased learning outcomes.

- Representation matters. An important way to create a sense of belonging is to choose inclusive course content so students can see themselves in your course materials.

- Every educator has a responsibility for inclusion. All instructors have a duty to provide equitable access to materials and a safe and welcoming space for all students to learn.

- Identities matter. Identity is complex and multifaceted. Understanding intersectionality will help you reflect upon how your and your students’ identities can impact the classroom environment and individuals’ learning experiences.

- Equal access for all students is essential. Apply concrete approaches such as UDL to address the challenges of creating an inclusive classroom for all your students.

References

Ahmed, S. (2006). The Nonperformativity of Antiracism. Meridians, 7(1),104-126. https://doi.org/10.1215/15366936-8565957

Ambrose, S.A., Bridges, M.W., DiPietro, M., Lovett, M.C., & Norman, M.K. (2010). How Learning Works: Seven Research-Based Principles for Smart Teaching. Jossey-Bass.

Barkley, E. F., Cross, K. P., & Major, C. H. (2014). Collaborative Learning Techniques: A Handbook for College Faculty. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons.

Boysen, G. A., & Vogel, D. L. (2009). Bias in the classroom: types, frequencies, and responses. Teaching of Psychology, 36(1), 12–17. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1080/00986280802529038

Johnson, D. W., Johnson, R. T., & Smith, K. A. (2014). Cooperative Learning: Improving University Instruction by Basing Practice on Validated Theory. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching, 25(3&4), 85-118. Retrieved fromhttps://proxy.lib.ohio-state.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=eric&AN=EJ1041374&site=eds-live&scope=site

McKeachie, W. J., Svinicki, M. D. (2002). Teaching Values: Should We? Can We? In W.J. McKeachie and B.K. Hofer (Eds.), McKeachie’s Teaching Tips: Strategies, Research, and Theory for College and University Teachers (11th ed.). Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

Plank, K. M., & Rohdieck, S. V. (2007, June). Thriving in Academe: The Value of Diversity. NEA Advocate, 24(6), 5-18.

Steele, C. M. (2011). Whistling Vivaldi: How Stereotypes Affect Us and What We Can Do (Reprint ed). New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company.

Walton, G. M., & Cohen, G. L. (2011). A Brief Social-Belonging Intervention Improves Academic and Health Outcomes of Minority Students. Science, 331(6023), 1447-1451. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.1198364