As an educator, how often do you think about copyright?

Consider these questions:

Have you ever avoided sharing useful and interesting material in your course because you were concerned about violating copyright?

Gotten confused navigating what constitutes "fair use" of an image, video, written work, or quote?

Or perhaps you learned after the fact that you actually shouldn’t have shared a particular work with your students? Oops...

Don't stress—you’re not alone. Copyright laws are complex and can be frustrating for many instructors to navigate.

From understanding fair use to using public domain, Creative Commons, and licensed works, this guide provides helpful resources and advice so you can confidently share copyrighted materials in both your in-person and online classes.

Copyright basics

Copyright is a bundle of rights that protect original works of authorship. It includes the right to reproduce, create derivatives, distribute, publish, perform, and display a work. Copyright was established in the U.S. Constitution to "promote the progress of science and the useful arts" (U.S. Const. art. I, § 8) by giving authors control over their works for a limited time. Along with the exclusive rights given to authors, specific exemptions, such as fair use, were written into the law for creating, using, and sharing copyrighted works.

Copyright protection is automatic. Once a work is fixed in a tangible medium of expression—so as soon as it’s written in an email, captured on film, saved to a computer, and so on—it is protected by copyright. Copyright protects most creative expression including literary, musical, and dramatic works, as well as sculptures, sound recordings, motion pictures, computer programs, architectural works, and more.

Why should you care about copyright?

On the surface, it might seem like an unnecessary roadblock for instructors and students, but copyright plays an important role in education. Copyright helps authors and scholars monetize their work. It gives creators the ability to protect their work from unlicensed or unauthroized use and provides an incentive for intellectual creativity. And, for you as an instructor, a strong understanding of copyright will open doors for you to enliven your teaching with meaningful new course material.

If you're hitting copyright roadblocks, there are many resources and exceptions to continue your teaching and learning efforts in the classroom and online. These resources explored below include open works such as public domain and Creative Commons materials, and limited statutory exemptions for in-person and online teaching (§ 110(1)-(2)) and fair use (§ 107).

Public domain

The public domain consists of works that were never or are no longer protected by copyright. Copyright protection has a set duration so copyright can expire, or never exist in the first place, in the case of ideas, facts, and discoveries. Public domain works are generally free to use in any way because copyright no longer applies and permission from the copyright holder is unnecessary. The public domain supports creativity and allows people to build off the prior work or knowledge of others, which makes these works ideal for teaching. Standards for academic integrity and plagiarism still apply when you use public domain works, so it is a best practice to use a citation whenever using someone else’s work.

There are a vast array of works in the public domain to support or supplement your teaching. Not everything in the public domain is old or already known. For example, works created by U.S. Federal Government employees in the scope of their employment are considered public domain. It is important to verify the public domain status of a work and use your best judgment when linking or sharing works. Copyright laws vary by country, so something in the public domain in the United States may not be in the public domain elsewhere, and vice versa.

Learn more about locating works in the public domain and openly licensed materials.

Use case #1

An instructor is looking to share resources on infectious diseases. They want to create an activity that helps future health care professionals practice identifying symptoms in at-risk populations. Using materials from the Center for Disease Control, they create a branching activity that walks students through the process of recognizing and diagnosing flu symptoms in at-risk individuals and charting a care plan for different scenarios.

Use case #2

An instructor is transforming their Introduction to Philosophy class to an online course. One of their favorite components of their in-person class is the robust discussions and in-depth textual analysis. These texts can be complex and intimidating for students. An instructional designer colleague recommends social annotation assignments to allow students to comment, critique, and ask questions about the readings. They find online versions of Plato’s and Socrates’ writing to upload to the web annotation tool, which is possible since these works are in the public domain.

Creative Commons

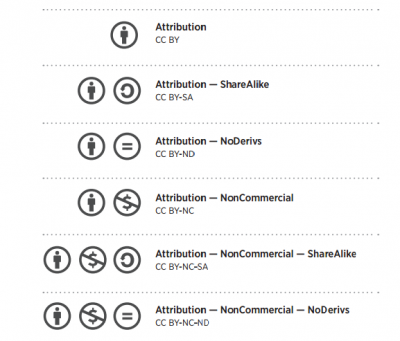

Creative Commons (CC) works fall in the spectrum between all rights reserved and public domain. These works are protected by copyright, but creators choose licenses that tell users when and how they can use the work.

There are six primary Creative Commons licenses that can be used in different combinations. All CC licenses require attribution and there are specific elements to include in the attribution statement, such as the author, title, source and license. Most attribution statements follow the same patterns as academic citations. Attribution is a license term—without providing an attribution statement, the permissions and terms of the license don’t apply. Creative Commons licenses require that attribution be made in a reasonable manner, so there are no hard rules on where you place the attribution statement or in what order you list the elements.

Creative Commons works are well suited for both teaching and research. For example, Creative Commons is a great resource for adding stock or decorative images to your courses or scholarly presentations. Many open access articles and open educational resources are also licensed using Creative Commons.

Learn more about how to use Creative Commons licenses in A Simple Guide to Creative Commons.

Use case #1

An instructor is looking to add more creativity to their class. For a unit on social psychology, they want students to explain their research questions using videos posted to a Carmen discussion board. They introduce a brief lesson on copyright and Creative Commons to show students how to use works appropriately and what rights they have as student creators. For the video assignment, they require students to use only public domain or Creative Commons works. They link to the Creative Commons search interface and resources on Creative Commons images, music, and audio. They also link to information on Creative Commons to show students how to openly license their videos if they choose to do so.

Use case #2

An instructor is teaching an advanced mathematics course. The course is set in a sequence and the instructor finds that many students are forgetting key concepts learned in a prerequisite course. The instructor wants to add a brief unit reviewing those concepts to set up a better foundation for their course, but they do not want students to have to buy any additional materials. They find a textbook on the Open Textbook Library so students can review and practice earlier concepts. Because the textbook is openly licensed, they also reformat the practice problems from the textbook into a Carmen quiz so students can demonstrate their knowledge.

Library licensed works

University Libraries has license agreements in place for various types of resources, including ebooks, journal articles, streaming video, and more. If the course materials are already available to students electronically, connect with a subject librarian. Most electronic resources through the library allow materials to be linked directly within a Carmen course.

Access to library resources is managed by IP (network) address so that access is seamless when a user is on campus. When off campus, users must sign in through the proxy server to access resources. This makes it a little more complex to provide URLs that work from both on and off campus, especially when using database resources.

Sharing these resources is easiest with the permalink or permanent link, which are stable links to resources in the library’s collections. Using these permalink or permanent links reduces the chances of broken links in your course and provides easier access to library resources for students. By adding the Ohio State proxy server string to a permalink, your off-campus students will be able to easily authenticate and be able to access the library resources without having to navigate to the resource on their own. Those links are also helpful for the Libraries to better understand what resources are being used.

For more information on locating permalinks and adding the proxy string to a URL, see Linking to Library Licensed Resources.

Use case #1

A nursing instructor is redesigning their course and realizes the textbook they have been using for years is no longer meeting their needs. They are also looking to create a more affordable course for students. They connect with their subject librarian and replace the textbook with journal articles and resources available from University Libraries. Using permalinks, they embed the resources directly into Carmen, so students know what articles and chapters to read. The subject librarian also found videos from the library’s streaming video databases that they were able to embedd directly into the course.

Use case #2

In their journalism course, an instructor wants to assign current event reflections on a biweekly basis. Every other week students must find a current article or news piece and critique it based on concepts learned in that week’s lesson. Using library databases, the instructor links to popular sources such as The New York Times, The Washington Post, Nexis Uni, and The Wall Street Journal so students can find articles for free and share them in discussion boards.

Educational exemptions

Educational use has a specific exemption carved out in the law. Sections 110(1) and 110(2) of the United States Code cover the performance and display of copyrighted works in face-to-face and online classrooms. Section 110(1) applies to physical classrooms or classroom-like environments and gives instructors clear space to perform or display any works, but only covers nonprofit educational institutions for in-person teaching activities.

Section 110(2), also known as the Technology, Education, and Copyright Harmonization (TEACH) Act, covers teaching in online and distance environments. Because teaching online allows for broader dissemination of works, copyright use is more restricted for online courses. The TEACH Act enables exceptions for the digital transmission of copyrighted materials by accredited, nonprofit educational institutions. To comply with TEACH, the law requires academic institutions to meet specific criteria for copyright compliance and education. As an instructor, you must also follow a set of guidelines that mediate the performance and display of material.

These educational exemptions only cover performance and display of work such as a sound recording of a poem, displaying images in a PowerPoint, or sharing a legally acquired film clip. They do not cover the reproduction or distribution of works like PDFs, textbooks, or readings.

If your use case does not meet the requirements of the TEACH Act (§ 110(2)) or face-to-face classroom performance or display (§ 110(1)), it may be possible to still rely on fair use, which is explained below.

Use case #1

An English instructor wants to compare the 1853 memoir "12 Years a Slave" with the 2013 film of the same title. They have students read the text and set aside an entire class period to discuss it. After the discussion, the instructor wants to show clips from the film. The text is in the public domain, but the film is still protected by copyright. Since this is a unit they teach multiple times a year, the instructor owns a DVD copy they purchased. Using the technology available in Denney Hall, the instructor shows clips from the film to continue the discussion on the material. Because this is an in-person class, with a legally acquired DVD copy, the instructor can display clips from the film to students under Section 110(1).

Use case #2

An art history instructor wants to give a lecture on the influence of Van Gogh on modern artists. Many of Van Gogh’s works are in the public domain, but modern works are likely protected by copyright. To share this with the class, the instructor makes a PowerPoint with images from Van Gogh and various modern artworks. The PowerPoint is only made available in Carmen to enrolled students, and the instructor reminds students to not share or download course content beyond their own individual study needs. If the amount is comparable to a live classroom session, the TEACH Act permits the instructor to share images of modern art in a PowerPoint for their online class.

Fair use

Fair use is a critically important exemption in education. It is relied on in so many different situations, from something as simple as a quote in a paper to support an argument, to a sketch comedy skit performed on live TV.

Unlike other exemptions in the law that can be very specific and explicitly identify the conditions for their application, a fair use analysis works by balancing four factors: purpose, nature, amount, and market effect. You evaluate these four factors on a case-by-case basis for each work and each use case to determine if it is "fair."

Compared to other statutory exemptions (like TEACH), fair use is relatively flexible and can be applied to new technologies or teaching methods. Fair use of a work is not considered an infringement, but only a court of law can officially determine fair use.

There are steps and best practices to follow to determine fair use and strengthen your fair use argument. Carefully consider each factor described below.

Purpose

The first fair use factor asks you to consider the purpose of the use. The law outlines some illustrative examples such as commentary, criticism, news, parody, teaching, research, and scholarship. A critical component of this factor is also considering transformation or the degree to which the copyrighted work has been changed or given a new meaning, message, or purpose.

Transformative uses help to support your fair use argument. For example, if a work was originally intended to be used for entertainment but you are now using it as a teaching tool with commentary and criticism, that may be a transformative use. On the flip side, scanning and uploading a printed textbook to Carmen so students can access it electronically does not likely qualify as a transformative use—the purpose is educational in both forms and has not changed.

Nature

The second fair use factor to consider is the nature of the copyrighted work. Highly creative works, such as fiction books, music, and films, are closer to the core intent of copyright protection. Using these creative works may weigh against your fair use argument as compared to works that present as more factual, such as textbooks and research articles. Courts also tend to be more protective of works that are not yet published, so sharing unpublished material may weigh against fair use, too.

Amount

The third fair use factor to consider is the amount and substantiality of the portion used. This factor encourages you to consider how much of a given work is needed to achieve your purpose, as well as whether you are using the “heart of the work.” The “heart of the work” is the portion of the work that is likely to hold the most value. Using the “heart of the work” can weigh against fair use.

The amount of a work you use should be reasonable for your teaching purpose. In some cases that may be an entire work, as when you need to display an entire image to effectively teach a concept. In contrast, consider how much of a written work is needed for students to read; for example, just a portion or chapter of a book may achieve your outcome. If students only need access to certain sections, scanning and uploading the entire book would weigh strongly against fair use.

Effect

The fourth and final factor to consider is the effect the use will have on the market for the original work. If your use substitutes for the original work, you run the risk of substantial market harm and this will weigh against a fair use argument. For example, if there is a readily available market to license or pay for a work, providing that material for free on a public site so anyone can access and download it could count as a substantial market harm.

Transformative use can also come into play when considering the fourth factor. The more transformative your use of a work, the less likely it is to cause market harm because the original and new works will occupy different markets and serve different purposes.

It's important to remember that there are no shortcuts or bright-line rules written into the law for fair use. It’s common to hear misconceptions like, "All educational use is fair use," or "Using 10% of any work is okay," but guidelines like these do not exist in the law. Indeed, not all educational uses are fair use and sometimes using a whole work or substantial part can still be fair use. The best approach is always to thoughtfully balance the four factors described above based on your specific intended use.

Use case #1

A social work instructor finds an infographic that demonstrates the socioeconomic connections between public health and zip codes. This infographic displays the information in a way that is easy to understand and accessible for students. She decides to use this as a model and assign students to create their own infographic based on the data presented in the published research. She downloads a copy of the infographic and shares it with students in Carmen to go over assets of the infographic that work well and showcase the creator’s design choices. She provides a citation and link to the original work. After reviewing the fair use checklist, the instructor believes the use of the infographic to teach concepts of information organization and graphic design favor fair use.

Use case #2

A new economics instructor disagrees with the high price of textbooks, but their college requires them to assign a textbook for their course. To protest these costs and save students money, they scan and upload five chapters of the textbook to Carmen. They think because it is educational and behind Carmen authentication, no one will ever know. But if the instructor were to look at the fair use checklist, they would discover this is likely not fair use. Although access is limited to enrolled students and the purpose is educational, the amount used and market effect lean heavily against fair use—arguably, the scans negatively impact the market for the textbook.

Permissions

If your use of a copyrighted work doesn’t fall under one of the educational exemptions or fair use, getting permission from the copyright owner is the next step. The first part of this process is to identify the copyright owner—often, but not always, the author or creator. Note that copyright can be transferred to another owner, and it can also be held by an employer or commissioning part, known as work made for hire. Sometimes a work may have multiple authors or separate rights to different underlying works. Identifying the copyright owner(s) can also differ depending on the industry or format.

After you identify the copyright owner, the next step in the process is to identify what rights are needed. Remember that copyright is a bundle of rights that includes rights to reproduction, distribution, adaptation, public display, and public performance. Asking for the appropriate rights may be crucial to securing permission. It can be a balancing act to consider the rights of creators and users, and it may require negotiation and payment. The most important thing when securing permission from a copyright owner is to get it in writing. Even an email can be okay if it thoroughly addresses the exceptions of all the parties.

There are also templates available through Copyright Services that may be used to help you draft your permissions requests.

Use case #1

An engineering instructor is teaching a unit on material design. Their colleague from another university is authoring a book on this topic that has some practical application the instructor would like to incorporate into their course. The instructor knows the colleague’s book has been written but will not be published until next fall. The instructor reaches out to the colleague to see if they could use a chapter of the book in advance of publication. The colleague checks their publishing agreement, which allows them to share preprint copies of the work at their discretion. The colleague gives the instructor written permission to use the unpublished chapter for next semester until the book is published and a library copy is available.

Summary

Being informed about copyright and following best practices can empower you to enliven your course with a range of new material.

- Copyright is automatic and helps to balance the needs of users and creators

- Public domain and openly licensed works, such as through Creative Commons, are great resources to incorporate into your teaching

- Educational exemptions in the law exist but require specific circumstances with strict guidelines

- Fair use is always an option; make sure you have a strong fair use argument by balancing four factors: purpose, nature, amount, and effect and use the fair use checklist to guide your analysis

- Permission from a copyright owner can be secured when you don't have an educational exemption or fair use, but it may require negotiation or payment

For further assistance with matters pertaining to copyright law, fair use, and permissions, contact Copyright Services at libcopyright@osu.edu.